These hubs provide reliable energy during blackouts

The inspiring story of New Orleans’ Community Lighthouse Project

As more and more natural disasters strike the US, the resourceful citizens and churches of New Orleans are showing the country how citizens can protect themselves during the power outages that typically come with such storms by using solar-powered community “lighthouse” hubs as reliable sources of energy and refuge during blackouts.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, inundating nearly 80% of the city’s urban areas after its levees collapsed. One of the hardest hit neighbourhoods was St. Bernard Parish, a close-knit, working-class community perched between New Orleans and the wetlands leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Its population dropped from about 67,200 to about 35,900 in 2010, because so many homes had become unlivable.

Two volunteers, a lawyer and a teacher, came to help, and ended up creating a nonprofit (originally the St. Bernard Project, now SBP) that rebuilt many homes in the devastated parish and, with help from Toyota’s Production System, is now helping to reshape disaster recovery nationally.

Its first multi-family project, in partnership with the public utility Entergy New Orleans and AmeriCorps, provides a model for protecting lower-income residents from economic displacement during the longer-term recovery of their neighbourhood. The award-winning $7.4 million St. Peter Residential, a three-storey, 50-unit building in the Mid-City neighborhood serving veterans and low-income residents, has 450 rooftop photovoltaic panels and battery storage and was, its architects say, the first commercial building in Louisiana to achieve net-zero energy consumption.

The solar and battery system supplies backup power during natural disasters. Any excess electricity generated after the battery is full is exported to the city’s power grid. The solar panels can withstand winds of up to 144 miles per hour, and the battery system is mounted 3 feet above grade to protect it from floodwaters.

People in the city noticed that St. Peter’s power kept running in 2021, when Hurricane Ida knocked down all the major transmission lines connecting New Orleans to the broader grid operated by Entergy, blacking out the city, and causing nearly one million people in Louisiana to lose power. Thirty people died.

Residents realized that if anyone was going to solve the problem, it would be them. Broderick Bagert, lead organizer for Together New Orleans, said that as the city struggled to address basics like collecting garbage in Ida’s aftermath, they decided it was time to take on the responsibility themselves.

“For [Hurricane] Ida we were ready with showers, mattresses, shelter and food, but once again the electricity was out so we couldn’t serve our community,” said Antoine Barriere, senior pastor of Household of Faith Family Worship Church. “The power was the missing piece. We realized that we had to stop waiting for a fix and do it ourselves. We need to get off the grid and be self-sufficient, as with climate change we’re going to get more disasters.”

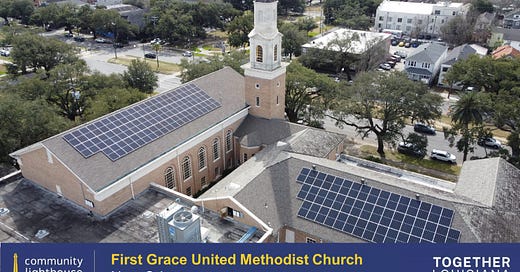

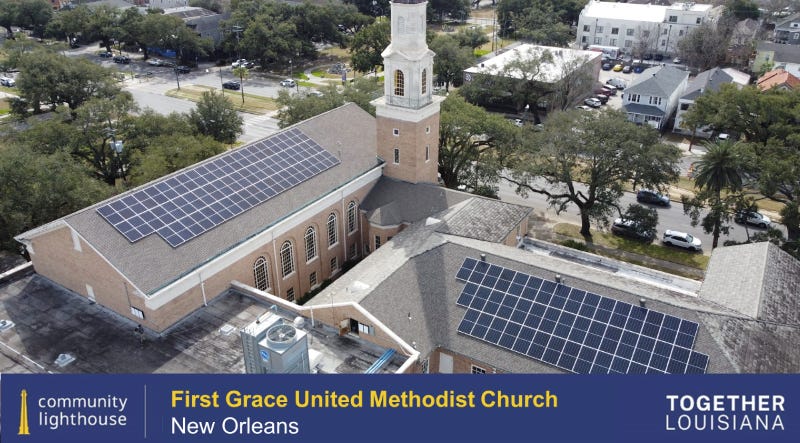

So Together Louisiana, a coalition of civic and church organizations, launched the Community Lighthouse Project in 2022. Funded through donations and government grants, the lighthouses are resiliency hubs that provide nearby residents with access to electricity, refrigeration, shelter, medical services and other basic needs during power outages and other disasters.

The idea behind the $13.8 million project is to install rooftop solar and backup batteries in 16 churches and community centers in New Orleans, situated so that every city neighbourhood will be within 15 minutes walk of a lighthouse. Each will have enough solar and battery capacity to supply more than a week of electricity for refrigerators, cooling centers and charging for cell phones and medical devices such as oxygen machines, medication nebulizers, home dialysis, infusion pumps, and other medical devices that depend on a reliable power supply.

From the lighthouses, teams of volunteers can fan out across neighborhoods and help people stranded by flooding or who can’t afford to evacuate. Each team will know who has health problems and who needs medication refrigerated or depends on electric wheelchairs for mobility, and should be able to connect with all of its neighborhood’s vulnerable people within 24 hours of an outage, says Bagert.

The project envisions the creation of a community-wide network of 85 to 100 resilience hubs across Louisiana, each powered by commercial-scale, rooftop solar systems with back-up battery capacity.

Last month, the first 10 lighthouses - nine in New Orleans and one in LaPlace - passed their first real world test when Hurricane Francine, a Category 2 storm, hit the coast of Terrebonne Parish, knocking out power to nearly a half-million people statewide. The following morning, Sept. 12, all 10 “community lighthouses” were up and running, the Louisiana Illuminator reported.

About 500 people sought refuge at the lighthouses after Francine, and Together Louisiana also delivered food and water to elderly residents at the Redemptorist apartment building in New Orleans’ Lower Garden District, which was without electricity for two days.

Nineteen people sought shelter at the New Wine Christian Fellowship, the only community lighthouse in LaPlace, which was one of the areas that had been hit hardest by Ida. Fortunately, Francine was not nearly as bad as many had anticipated, said Pastor Neil Bernard.

“Hurricane Ida sparked something in Southeast Louisiana,” says Logan Atkinson Burke, executive director of Alliance for Affordable Energy, a community advocacy group and Together New Orleans member. The increasing availability of rooftop solar and backup batteries “is enabling dreaming, if you will, about what resilience could actually look like in our city.”

Pierre Moses, president of 127 Energy, the solar and battery project developer whidh coordinates the technical side, saw the same “sea change” in customers and community members he met after the hurricane. “Overnight, within a week, residents, laymen and grandmothers in New Orleans were starting to talk about black-start capabilities of power plants around the kitchen table.”

I think it's going to be 3 posts in the end about disaster recovery. One is about the immigrants who go from disaster to disaster helping people rebuild and recover; one is about the amazing story of SBP, which is interwoven into this post. I discovered SBP because I wondered what examples of solar panels/batteries that the folks at Together New Orleans had seen in action :)

Wow!

Thank you!